Jesus was a mad man

Jesus didn’t grasp the safety of strict order, the value of hierarchical tradition, or the dangers of contagious disease. He spoke with foreigners, scoffed at legality, chatted openly with women, and likened the highest trust in God as similar to the innocence of trusting children. He loved everyone but the important and the wise. And now, Jesus wanted his friends to die with him. All for the exasperating and egotistical promise of a life with him in paradise.

Jesus has to be stopped

http://www.usccb.org/bible/readings/042116.cfm

The tragedy of the Judas story shivers our souls. His dark, willful decision to betray Jesus, a friend who loved him, a friend who trusted him with the finances of his band of believers, goes beyond shock. It’s worse than that. It is uncomfortably familiar.

Jesus knew the propensity of this fellow called Judas, and still he selected him as one of the apostles. Have any of us allowed a friendship to play out to our own destruction? Why would we ever let someone destroy us; knowingly allow a friend to testify that we are the enemy? What if we knew exactly what would happen to us if we agreed to let a friend betray us? What lesson is to be learned by this?

Judas was not so different, though, from the rest of the disciples. Some of them selfishly argued which would be ranked higher than the others. Most of the apostles questioned Jesus about his sanity. It was James and John, called the Sons of Thunder, who were eager to attack rogue disciples preaching Jesus’ message. All of the apostles slept through Jesus’ passion. Peter denied even knowing Jesus when he faced pressure from the Roman and Jewish authority’s henchmen. Judas was apparently similar to the rest of them. He was just another wayward man, wasn’t he? The financial officer of the apostles was as much driven by Satan as Peter, who railed against Jesus when he predicted his own death. Right?

Not quite. Judas’ intentions were not just emotional, nor awkwardly sinister, nor a pathetic ignorance prevailing over a difficult truth. Judas went further than other doubters, like those who gave up on Jesus when he said his followers must eat his body and drink his blood. Judas saw a calamitous character in Jesus. Like the political and religious leaders, Judas believed Jesus had gone too far, and must be stopped. The interpretive genius of Jesus' scriptural prophecy didn’t convince Judas that he was on the wrong side of destiny, the one heading toward calumny, an underhanded and manipulative treachery.

When Jesus said he spoke to the disciples in "parables,” Judas heard “a secret code.” When Jesus claimed that the way to the Father was through him, Judas heard that Jesus' path was riddled with cultic discrimination and anti-Jewish ideology. When Jesus said he was, “I Am,” Judas heard the epitome of blasphemy.

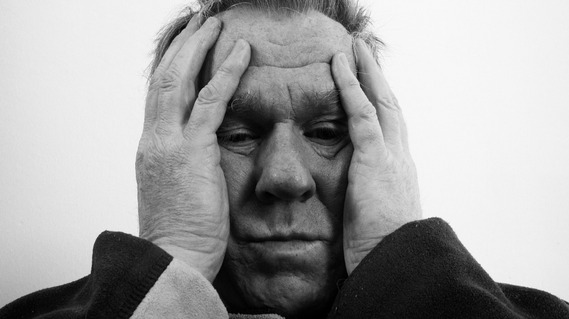

But more to the point, when Jesus spoke of his upcoming death, Judas didn’t make the connection between his own secretive designs and Jesus’ sacrifice. Judas saw a wasted martyrdom on the horizon. Jesus was not the man to be trusted anymore with leadership. Judas imagined a major shift away from success. After three years on a mission with great potential, the journey was ending with faithful men and women duped by a mad man. Jesus could cure the world, arouse multitudes, speak like a god, and now he was leading them all to their doom. The world couldn’t trust a man who spoke of death with sadness rather than spirited fight and justified honor. Plus, Jesus created chaos in the temple, flippantly paid the Romans with comically found coins, and obviously intended on upsetting the social order led by those who earned their rewards and fed the poor from their gracious leftovers.

Jesus didn’t grasp the safety of strict order, the value of hierarchical tradition, or the dangers of contagious disease. He spoke with foreigners, scoffed at legality, chatted openly with women, and likened the highest trust in God as similar to the innocence of trusting children. He loved everyone but the important and the wise. And now, Jesus wanted his friends to die with him. All for the exasperating and egotistical promise of a life with him in paradise.

Though Jesus had an uncanny ability to predict who was likely to be healed, or who had been improperly diagnosed as dead, Judas realized that Jesus believed in the miracles that took place. Jesus must be stopped.

If Judas was a reporter of today’s ilk, he would paraphrase the iconic story of “Man bites dog” to a whole new level. He would title his article, “Man betrays God.” Judas couldn’t just walk away from Jesus, incredulous and disappointed. Judas couldn’t just wave Jesus off as silly and ridiculous. He saw more than foolishness. Jesus recklessly called the wrath of God upon his own followers, and celebrated the eventual dismantling of the Jewish nation. In his own mind, it was not Judas who invoked treachery and treason. The crazy and dangerous person was Jesus.

How does one get so wrapped up in treachery? The analogy of the slowly boiled frog is false. A frog cannot be slowly boiled in a pot. It will leave. Judas was not slowly framed or formed, in other words, against his will. Each step in his descent was a willful retreat from truth into deceit. Anger and vengeance require practice, certainly, but a dutiful disregard and disdain, even a disgust for Jesus took purposeful steps away from the man who reached out to him. At the core, Judas decided against Jesus’ preaching about the benevolent power of divinity, the loving authority of the creator, and God’s all-encompassing guidance.

Have we ever gone this far? Most of us probably stop at scoffing, questioning the likelihood of a good God who is in control. We don’t see a world that reveals good outcomes, and so we toss away the unsupportable logic of a powerful God. We may not translate positive turns in our life as kind acts from a loving God, but few of us seem set against God, devising ways to eliminate him from the public conscience. We might consider goodness as an eventuality, a consequence in the balance of good and bad luck. But we don’t believe bad luck is what we should expect for ourselves. We don’t consider our luck as God’s playful or even dramatic guidance, because God doesn’t seem to be the source of our path. We could go that far. We could claim God isn’t paying attention. We might even walk away. But would we seek to destroy the God we’re unhappy with?

Oh dear. Maybe we have.

And yet, benevolent power, loving authority, and all-encompassing guidance was the entire purpose of Jesus’ ministry, regardless of what people imagined. God became one of us so that we would know him as all those things. If we know Jesus, we know the father. If we know about Jesus, we then meet his Spirit. Jesus is all about relationships.

Judas exemplifies for us the fear of such a positive relationship. Judas doesn’t bravely take disdain to it’s forgone conclusion, though, as if he is a hoodwinked martyr for God’s opposition. Judas is a willing accomplice, duplicitous rather than duped.

Alas, we are capable of being like him.

When we refuse to except God’s power, shun the experience of God’s love, and shout over God’s guidance, then we are prime candidates for another voice that more appropriately speaks to our negativity. In such a place, we actually desire the worst, as a proof of our caustic appraisal of the world, and our dissolution with the God we don’t want to know. Each of our individual Judas paths, if fulfilled, reveal the ultimate direction of such hopelessness. It is shame in the face of a loving God, self-hate at the hands of benevolence, and suicidal escape from a God who wants to be part of our innermost being.

Judas’ story, though frighteningly familiar to the dark times in our lives, shows us the closeness that God maintains with all of us. Even as Judas planned his final betrayal, Jesus shared his most intimate moments with him. Jesus involved Judas in the formation of the future for all mankind. Judas shared in Jesus’ final meal. Jesus kept him among his closest friends for as long as possible, yearning for his awakening, and yet resigned to allow Judas to do what he desired to do.

A simple extending of our hand to God in our darkness will change everything. Giving in to God rather than to what we know is evil will amend our path. Even as we repeatedly fall back into darkness God does not abandon his hope for us. God goes with us, even to those awful places. He only lets us go when we tell him we are done with him. And even then, he turns to face us, and accepts our betrayal with a kiss on the cheek.

What a kindness he offers us, to be the quiet accepting one in our moments of terror and hatred. Even amongst our friends, Jesus will not betray us. It is only our own obstinate betrayal that seals our fate.

But Paul, who murdered Christians, and certainly more egregious in his anti-jesus fervor, was salvageable. Why not Judas?

Indeed. How could anyone fall that far, we shake our head in disbelief. And then, we nod to ourselves. We remember the awful moments of retreat from God. All we need do, though, is reach out our hand to God. None of this dark end is necessary for God — the benevolent, loving, and comforting one who calms our hearts in order that we let him in. Our descent into hopelessness is only necessary if we demand it. No one else wants that for us.

Let the darkness go, he tells us.